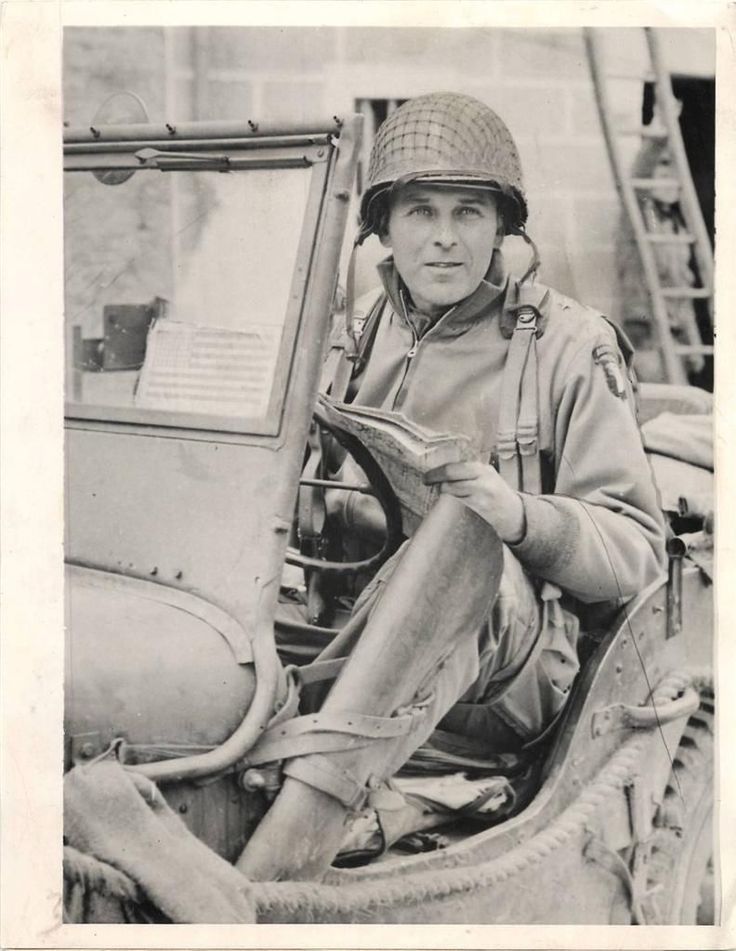

Maxwell Davenport Taylor was born in Keytesville, Missouri on August 26, 1901. He graduated 4th in his class at the West Point Military Academy in 1922 and received the rank of Second Lieutenant assigned to the engineers in June 1922. There he met a certain Matt Ridgway with whom he played a lot of tennis. From 1922 to 1926, he was stationed in Hawai in the engineers. He then served in the artillery with the 10th Field Artillery from 1926 to 1927 with the rank of First Lieutenant. He studied French in Paris and was able to teach French at West Point. He then attended the Field Artillery School at Fort Sill in 1933, before joining the Staff College at Fort Leavenworth in 1935. That year he was promoted to Captain and left for China. Ridgway remembered him in May 1939 when he and Marshall participated in a long tour of South America to meet with the leaders of these countries on the eve of an inevitable world war. Taylor had a strong reputation as a linguist and diplomat. He received his promotion to major in July 1940 after attending the War College. He was then assigned to the 12th Artillery battalion, before leaving to work in the secretariat of the General Staff. Then came one of the turning points of his career. April 1942; the 82nd Infantry Division was probably the best division in the whole US Army. Its CO was a certain Omar Bradley who had forged it in his image, all discipline and rigor. His ADC (Assistant Division Commander) is Matt Ridgway. General Leslie Mc Nair, Boss of the US Ground Forces, was looking for someone to rebuild the 28th Division. He chose Bradley. Ridgway became CO of the All American. He chose an elegant and distinguished artilleryman, diplomat and linguist, Max Taylor, as his Chief of Staff. Taylor was only half happy, because Joseph "Joe Vinegar" Stillwell, knowing that Taylor spoke Japanese, made eyes at him to join his military mission in the Far East. It was Marshall who objected and sent Taylor to the 82nd Infantry. On August 15, 1942, the 82nd Infantry Division "All American" was chosen to become the first US airborne division. It was actually split in two to provide the cadres for another airborne division, the 101st under Bill Lee. In early September, the division left Camp Claibourne for Fort Bragg. Ridgway was not entirely satisfied with Taylor. He considered him a nerd more interested in the intellectual side of things. Doc Eaton, Ridgway's future chief of staff, worked in Taylor's office at Bragg and described Taylor as "the smartest man he had ever met. He said that Taylor spent 10 minutes in the office and the rest of the time on the artillery ranges. In February 43, the 11th Airborne Division was activated; Joe Swing, Artillery Commander of the 82nd, took command, leaving Taylor free. He was given the task of creating the Table of Organization for the airborne artillery, both glider and parachute. With the integration of the 505 PIR into the 82nd Airborne, three of the most promising figures of the Airborne were reunited, Ridgway, Gavin and Taylor Bill Moorman, G-4 of the division and later of the XVIII Airborne Corps, said of these three "giants": "Ridgway could cut your throat and burst into tears. Taylor could cut your throat and stay still. Gavin could cut your throat and then burst out laughing..." In late September 1942, Ridgway decided to inspect his parachute regiment, the 504 at Bening. He also decided that it was time for him to face the singularity of his division: the jump! His entire staff volunteered, Joe Swing, Bud Miley (ADC) Doc Eaton, Bill Moorman, Don Faith, Ridgway's historic aide-de-camp ... and Taylor. It was Warren Williams, CO of 1/504 who served as jumpmaster of the first stick, and a certain Julian Ewell (future CO of 501), who officiated in the second. "It was like jumping off a train going 70 miles an hour onto a concrete road. When I got to the door, I was petrified; the jumpmaster said go and gave me such a kick in the Q!!! I jumped 10 feet in the air!" said Ridgway. Taylor, future CO of 101st AB, simply hated it; "I must have been drunk when I volunteered for that jump!" Ewell, who jumped right after Taylor, says his boss landed...head first! Ridgway would make a second jump a little later in '42... and would not jump again until June 6. Ditto for Taylor, who made his second jump on D Day (it takes 5 to qualify a paratrooper...). The lack of enthusiasm of these two leaders for the jump was to play against the Airborne in the aftermath of Husky and the disastrous jumps in Sicily, and a confrontation between Ridgway-Taylor on the one hand, and Gavin-Tucker (CO of the 504) on the other. The latter were fervent advocates of the paratroopers, while Ridgway considered that, given the Air Corps' inability to do the job, the Airborne should be reduced to the gliders. Taylor was not convinced of the effectiveness of the "vertical envelopment" doctrine. Ridgway changed his mind when he came to the aid of his friend Mark Clark, who was trapped in the Salerno pocket in September 1943, with the full force of his two parachute regiments. August 1943; the Italian government started secret talks with the Allies in order to negotiate the surrender of the Italian armies. Marshal Badoglio's envoys to Mostaganem to General Eisenhower feared German reactions. They insisted that the Allies take Rome by airborne action. On this condition alone, they agreed to surrender when the Allies landed at Salerno. The Allied generals, Eisenhower, Alexander, Beddel Smith and Montgomery, envisaged dropping the 82nd Airborne Division on five Roman airfields that the Italians would have secured beforehand. Ridgway and Taylor doubted the feasibility of such a plan. There were more than 25,000 Germans around Rome, and Italian reactions, especially from anti-aircraft defences, were unpredictable. Ridgway defended himself with all his energy and at the risk of his career against this plan, which, according to him, was equivalent to the destruction of the 82nd Airborne. He managed to convince Alexander to send a secret observer to Rome to test the real intentions and powers of Marshal Badoglio in Rome. Max Taylor, Ass Division CO of the 82nd Airborne, volunteers for this James Bond-like mission. Taylor, a great diplomat, speaks several languages... and is still not a qualified paratrooper! The 82nd began its transfer from Tunisia to the airfields of Sicily from where it was supposed to take off for the assault on Rome. An improbable mission then began, against the clock, for Maxwell Taylor who, accompanied by Colonel William T Gardiner, 51 years old, Intelligence officer of the 51st TC Wing, had to infiltrate occupied Rome to meet the Italian government. On September 7, 1943, at two o'clock in the morning, the two men boarded a British PT boat in Palermo. This one took them to the island of Ustica, where a rendezvous had been arranged with the Italian corvette Ibis. They disembarked 300 km further north in Gaeta. There, they were disguised as downed Allied airmen and transported to Rome in an ambulance with tinted windows; 120 km on the Appia Way, crossing German patrols! In the early hours of September 8, Taylor met with Marshal Badoglio, head of the Italian government. The talks were held in French. The result of these talks was that the Italians were unable to control the airfields. Taylor sent a secret message to Eisenhower in Algiers, informing him that the conditions for the airborne operation on Rome had not been met. At 11:35 a.m. on 8 September, he sent a second message of confirmation. Taylor and Gardiner then boarded an Italian three-engine plane in the greatest secrecy. The most tense trip of Taylor's life began; to reach Algiers from Rome, aboard an Italian plane, without knowing what the reactions of the Luftwaffe and the numerous allied fighters patrolling the Mediterranean would be... Eisenhower then sent messages to the Paras of the 82nd saying that the operation on Rome was cancelled. When this counter order arrived, 62 planes were ready to take off.... Ridgway had saved the 82nd Airborne from a suicide operation. Doc Eaton, his Chief of Staff, remembers seeing him crying that night... On February 8, 1944, William Carter Lee, CO of the 101st Airborne, "father" of the US Airborne since the creation of the test platoon and the Airborne Command, was on maneuvers in England with Bud Harper (401st GIR). His ADC Don Pratt temporarily took command of the 101st. Eisenhower and Bradley chose Taylor, still in Italy. Taylor was not an airborne man, and his combat experience was limited. But he had forged the 82nd with Ridgway. He was a brilliant leader, and his secret intervention in Rome saved the Airborne from a disastrous operation on Rome. Francis March III would replace Taylor as the 82nd's artillery commander. Taylor saw in Italy what the Airborne was capable of. He became a strong advocate of the airborne weapon. When Marshall Leigh-Mallory intervened with Eisenhower to have the Airborne component (Op Neptune) of Operation Overlord cancelled altogether, Taylor, Gavin and Ridgway intervened violently to ensure that the attacks were maintained. Taylor was even among those who professed an airborne intervention BEHIND... Omaha!!! On June 6, Max Taylor landed in a field near Holdy. He joined a trooper of the 501st and quickly found Brigadier General Anthony Mac Auliffe, his Chief of Staff Higgins and a British war correspondent named Robert Reuben. Within minutes, Taylor found himself at the head of a small force of 85 men made up almost exclusively of staff, majors and captains. Taylor then marched to Sainte Marie du Mont and Exit No. 1, with "so many officers to command so few troops..." At 1:30 p.m. on September 17, Max taylor made his third ... and final jump of his career near Son north of Eindhoven. On November 26, 1944, the 101st Airborne took its quarters at Mourmelon. Taylor was called back to Washington for a series of conferences. He learned of the engagement of his division at Bastogne on the 18th and could not catch a plane until December 24th. On the 26th, he was in Paris. He asked to be dropped on Bastogne. Bedell Smith, head of the SHAEFF refused. He took a truck and arrived in Bastogne on December 27th via LUxembourg and Arlon.

Copyright ©2025 Réalisé par Alexandre Maurouard Freelance